Economics of Rare Earth Metals

Rare earth elements and critical minerals are vital for clean energy and technology. They form strong permanent magnets for wind turbines and electric vehicles (EVs), provide battery materials (lithium, cobalt, nickel) for high-density EV and grid storage, and are used in semiconductors, optics, defence, and medical systems. Demand is projected to triple by 2030 and quadruple by 2040 to meet net-zero targets, with clean energy systems requiring over 40% of rare earths by 2040. These “hidden” elements are crucial for modern EVs, wind turbines, solar panels, and electronics.

- Key applications include permanent magnets in electric vehicle motors and wind turbines (neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium); lithium-ion batteries (lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese); electronics (smartphones, laptops, semiconductor chips); and defence/satellite components (phosphors, alloys). These uses show why rare earths are often referred to as the “new oil”—their economic significance stems from powering clean, high-tech industries.

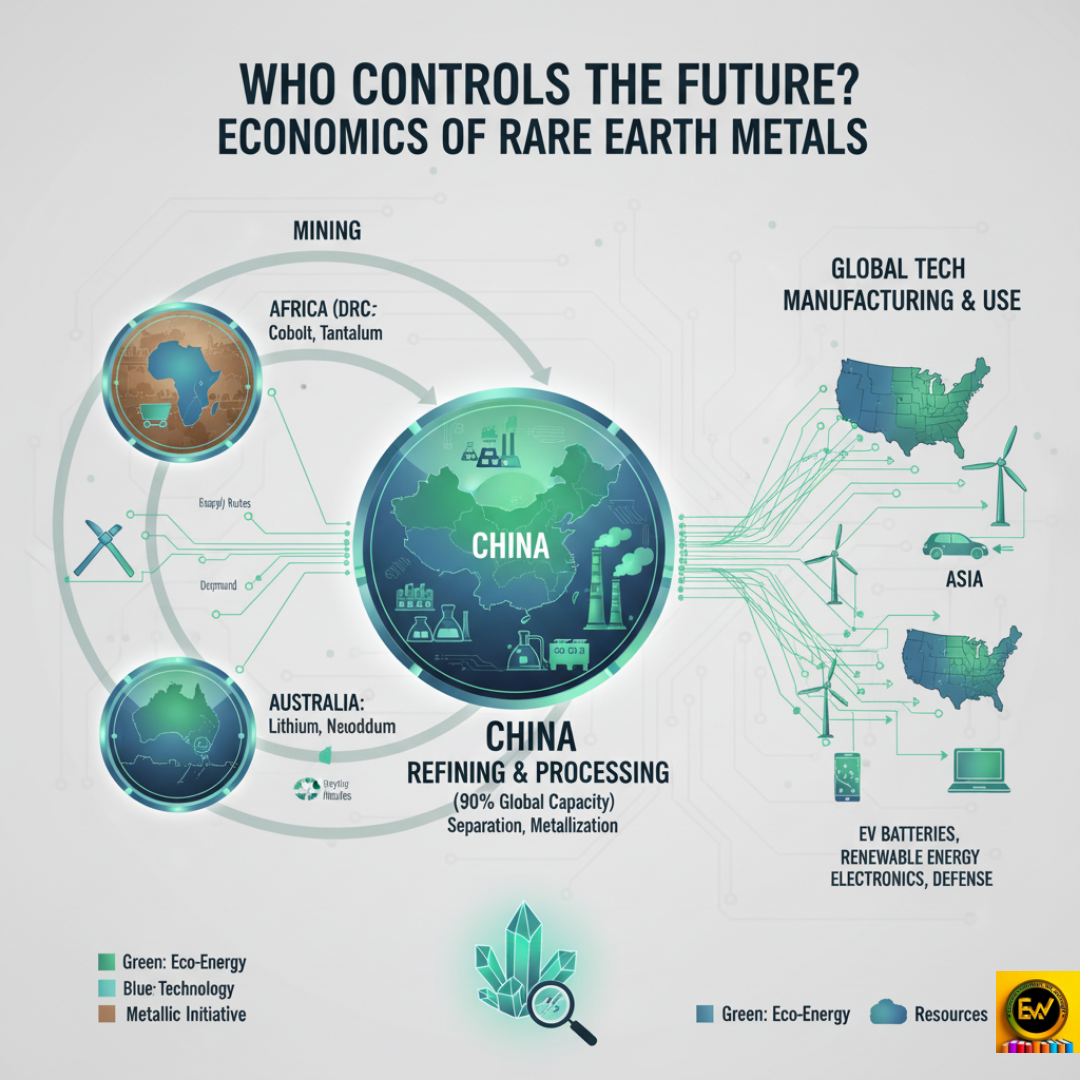

China controls most global rare earth reserves and production, dominating mining, processing, and manufacturing. This creates a fragile global supply chain, making rare earths strategically vital, especially with projected demand increases for clean energy components like lithium, cobalt, dysprosium, and neodymium.

Environmental and Economic Costs

Extracting rare earths is expensive and environmentally hazardous, involving open-pit mining and chemical leaching that produce massive amounts of toxic, sometimes radioactive, waste and wastewater. This waste can contaminate soil and groundwater, posing health risks. Stricter environmental regulations in countries outside of China now significantly increase the capital and operational costs for new mines and refineries, unlike China’s past weaker standards that allowed it to undercut foreign producers.

Current recycling and substitution efforts for rare earths are insufficient. Minimal recovery from electronics and batteries, coupled with inadequate technology and infrastructure, means we remain reliant on primary extraction, as highlighted by the World Economic Forum. Research into alternative battery and magnet chemistries, alongside efforts towards circularity, aims to reduce demand for raw materials. While promising, these innovations currently cannot keep pace with the rapid growth of green technology.

Geopolitical Supply Dynamics

China uses its control over rare earth mining and exports for geopolitical leverage, tightening regulations in mid-2025 and expanding export controls in April and October 2025. These actions, justified by national security, are seen as a response to U.S. restrictions, causing significant disruptions, production pauses for Western carmakers, and a 5-6x price surge.

China has historically used “rare earth diplomacy,” halting shipments to Japan in 2010 and considering cuts during the 2018-19 U.S.-China trade war. By controlling processing knowledge, China maintains other countries’ dependence. It remains the leading refiner for 19 of 20 critical minerals, including all rare earths, exemplifying resource exports as a bargaining tool.

| Mineral Value Chain | China | USA | Australia | DRC | Rest of World |

| REE Mining | ~70% | ~12% | ~8% | 0% | ~10% |

| REE Processing | ~91% | <1% | (Lynas in Malaysia) | 0% | ~8% |

| REE Magnets | ~93-98% | <1% | 0% | 0% | ~5% |

| Cobalt Mining | <1% | 0% | ~3% | ~76% | ~20% |

| Cobalt Refining | ~85% | 0% | 0% | <5% | ~10% |

Nations are diversifying critical mineral supplies, with the U.S., EU, Australia, and several African countries developing projects. India is also leveraging its reserves and collaborating for magnet production. However, China still dominates 95% of heavy rare earth processing. Analysts suggest creating thicker global markets with more sources and recycling to prevent supply shocks and reduce single-nation dominance.

Environmental and Economic Trade-offs

The unique geology and chemistry of rare earths mean their extraction often comes with significant economic and environmental challenges. Mining generates large amounts of waste and poses risks of pollution. For this reason, every new project must invest in costly pollution controls, such as lining tailings ponds and treating wastewater. These compliance expenses, along with changing market prices, have delayed or stopped many projects in the West. For instance, even a country with plenty of reserves, like India, is just now developing its industry because past extraction plans failed due to costs and environmental concerns. Essentially, clean energy can’t be immaculate unless its minerals are sourced responsibly.

Governments are enacting stricter environmental regulations, and investors are demanding sustainable mining practices. Proposals like carbon-adjusted tariffs aim to account for environmental costs. Tech companies and utilities are committing to responsibly sourced or recycled rare earths, shifting cleanup expenses to the supply chain. While stricter rules increase domestic prices, they also encourage recycling and efficiency innovations. Recycling and alternatives are crucial to reduce demand, even as new mines are opened.

Recycling, Innovation and Alternatives

No single solution will eliminate our reliance on rare earths, but advancements in technology could help. Recycling electronics and batteries is still in its early stages, but it is speeding up. Some automotive companies are designing vehicles to make it easier to recover magnets and battery packs at the end of their life. Governments are funding demonstration plants that chemically extract rare earths from discarded hard drives and magnets. Over time, widespread recycling could meaningfully increase supply, but currently, most rare earths still come from ores.

Battery and magnet innovations are rapidly progressing. Carmakers are testing magnet-free motors, while battery manufacturers are using nickel-rich or iron-based chemistries to reduce cobalt. New permanent magnets, like iron-nitride alloys, require fewer rare earths. If scaled, these could reduce demand for the rarest elements. Electronics companies are also pursuing recycling; Apple aims for 100% recycled rare earths in device magnets by 2025. These efforts suggest recycled rare earths could become cheaper. However, these initiatives take time. Currently, rare earths, lithium, and cobalt remain crucial, non-substitutable inputs. Diversification—through new mines, alternative suppliers, and recycling—is the best strategy to mitigate geopolitical and supply risks.

Future Trends: Industrial Policy and Self-Reliance

Rare earths are vital for green industrial policy, with countries like the U.S., EU, China, and India investing heavily to control their supply chains for technological sovereignty, even at higher costs. The U.S. has passed the Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS+Science Act, while the EU has the Critical Raw Materials Act. China has a state-led strategy, and India approved a ₹7,300 crore plan for rare-earth magnets and processing.

Resource nationalism offers both pros and cons. While it can secure local supply and create jobs (like in China). It risks higher prices for green products and trade conflicts. Over 3,000 new restrictions since 2021 indicate a shift from open markets. Supporters argue it’s vital for countries to control resources and benefit from the green transition.

Rare earth economics depend on policy and innovation. While recycling, alternative chemistries, and new technologies could ease supply pressure, demand rises with electrification. Rare earths are the 21st century’s “oil,” influencing sustainability and geopolitics. Securing reliable, green supplies will be crucial in the clean energy era.

Conclusion

Rare earth elements and critical minerals lay the unseen groundwork for the world’s green shift. They power the technologies that will shape the 21st century, including electric vehicles, wind turbines, modern electronics, and defence systems. However, their extraction and control come with significant environmental, economic, and geopolitical impacts. As countries push to cut carbon emissions, the competition for these resources has turned into a new kind of strategic rivalry. China’s control over processing and refining presents both an advantage and a risk in the global landscape.

Moving forward requires diversification, innovation, and sustainability. Creating strong supply chains through cooperation with allies, expanding recycling systems, and developing alternatives to rare earth materials are essential for ensuring energy security and maintaining technological independence. In the end, the countries that successfully blend economic development with environmental responsibility and technological advancement with geopolitical insight will guide the upcoming industrial age. In this light, rare earths are not merely the hidden drivers of green technology; they are key players in establishing a new global economic framework.