Black Gold of the Digital Age: Is Data the New Oil?

1. The Digital Age’s Defining Commodity

The 21st-century digital age offers convenience but raises concerns about privacy due to the continuous generation of data. Personal data is a valuable yet contentious asset, often referred to as “the new oil.” However, this metaphor is incomplete.

“Surveillance capitalism,” the dominant digital economic model, extracts human experience, imposing a “price of privacy” beyond financial costs. This leads to economic discrimination, psychological harm, social polarisation, and reduced free will.

This report analyses the “data is the new oil” metaphor, deconstructs surveillance capitalism’s extraction, prediction, and control methods, and outlines its individual and societal costs. It evaluates governance frameworks and countermeasures, concluding with a forward-looking perspective on an AI and IoT-influenced economy, advocating for a human-centred digital future.

2. Deconstructing the Metaphor: Is Data the New Oil?

The phrase “data is the new oil” has become a common way to describe the value of information in the 21st century. Journalists, policymakers, and executives often repeat it. Its appeal comes from its simplicity, painting a picture of a valuable, world-changing resource. However, to truly understand the data economy, we need to look past the catchy phrase. We must critically explore its origins, its strengths, and, most importantly, its significant weaknesses.

The Genesis of an Analogy

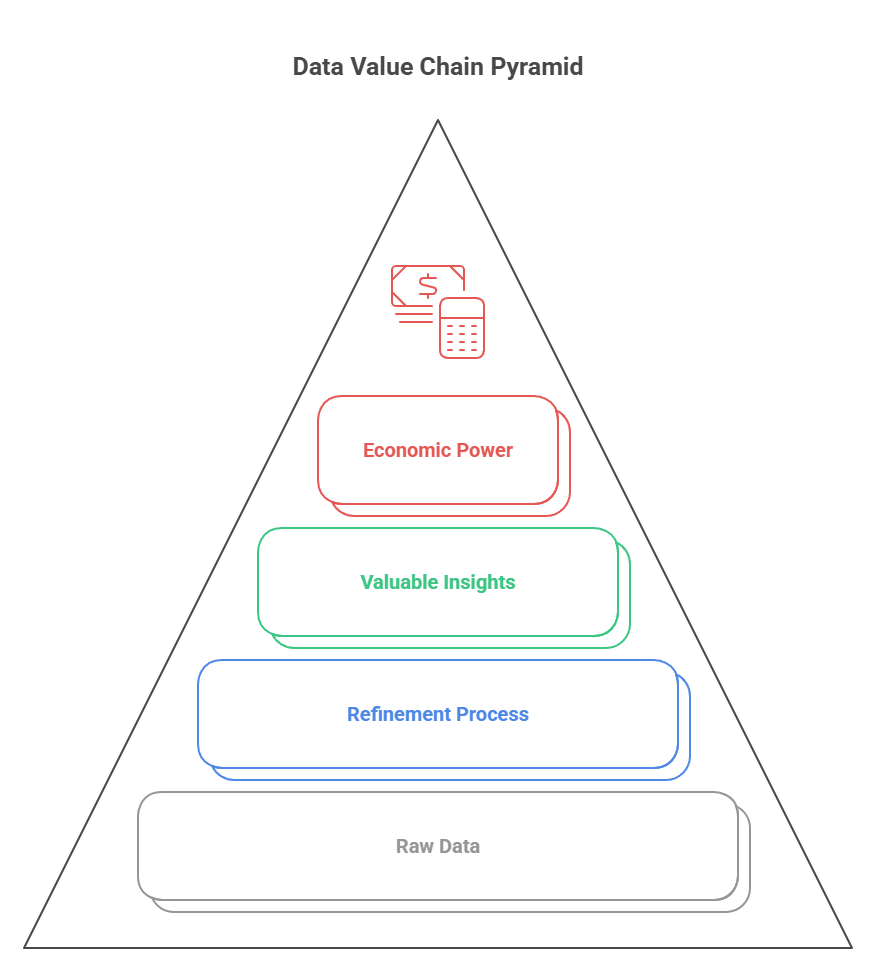

Clive Humby, a distinguished British mathematician and data scientist, originated the assertion “Data is the new oil” in 2006. He underscored the notion that raw data, akin to crude oil, holds no intrinsic value until it undergoes a refinement process. Humby, a co-founder of dunnhumby and key figure in the Tesco Clubcard’s development, recognised the strategic importance of processed data as a valuable corporate asset.

3. The Parallels: Where the Analogy Holds

The metaphor’s lasting relevance comes from clear similarities between the industrial economy driven by oil and the information economy driven by data.

- Fueling Economic Revolutions: Oil drove the Second Industrial Revolution, powering engines, transportation, and chemical industries. Similarly, data fuels the Fourth Industrial Revolution, driving AI, e-commerce, and analytics, fundamentally changing the global economy. Both resources are foundational to their eras..

- The Refinement Process: Humby’s analogy regarding oil refinement applies to the data value chain. Raw data, akin to crude oil, undergoes extraction, transportation, and subsequent refinement through processes such as cleaning, structuring, aggregation, and analysis. This “refinement” process converts raw data into valuable insights, models, and information products. In both scenarios, the refined product, rather than the raw material, possesses the inherent value.

- Concentration of Power and Oligopoly: In a parallel to the 20th century’s oil industry, where “Big Oil” established a dominant oligopoly, “Big Tech” now occupies a similar position within the contemporary data economy. Corporations such as ExxonMobil historically exercised control over the entire oil supply chain, accumulating substantial wealth and influence, reminiscent of figures like John D. Rockefeller. Presently, technology conglomerates including Google, Amazon, Apple, and Meta oversee the data infrastructure—encompassing extraction, refinement, and distribution—with the immense wealth of their founders underscoring the power derived from their command over the era’s most pivotal economic resource.

- Economic Dependence: Modern society exhibits substantial dependence on oil, which fuels transportation, supply chains, manufacturing, and the production of plastics. Similarly, data has become indispensable for businesses seeking to optimise operations, cultivate customer relationships, formulate strategic decisions, and customise services. E-commerce in the digital economy relies on continuous data flow and analysis.

Data Monetisation Models

| Model | Description | Example Companies |

| Direct monetization | Selling raw/anonymised data or analytical insights | Nielsen, Bloomberg, Equifax |

| Indirect monetization | Using data for internal efficiency, product improvement | Uber, Tesla, Google |

| Inverted monetization | Leveraging insights without directly selling user data | Referral partnerships (banks, hospitals) |

| Behavioral futures | Data used to modify/predict consumer actions; sold to advertisers | Facebook, Google |

4. Why Data Is Not the New Oil

The assertion that “data is the new oil” is fundamentally flawed. Data possesses inherent distinctions from oil; overlooking these differences invariably results in suboptimal business and policy decisions. Oil is a rivalrous and scarce resource: its use by one party prevents its use by another, and its supply is finite. Data, conversely, is non-rivalrous and abundant, permitting simultaneous utilisation without depletion, a characteristic pivotal to the scalability of the data economy. Indeed, an estimated 90% of global data has materialised within the preceding two years.

This key difference has several important implications:

- Value Lifecycle: Unlike oil, which loses value upon consumption, data often appreciates with use. Its reusability, combinability, and applicability to AI model training generate a cycle of increasing value.

- Replication and Transportation: Data, unlike oil, can be copied and transmitted globally at light speed through fibre optic networks virtually cost-free.

The assertion that “data is the new oil” is problematic due to data’s inherently non-rivalrous nature, which restricts its utility when accumulated. In contrast to the scarcity of oil, the profusion of data facilitates digital business models centred on maximising collection and harnessing network effects, thereby generating a “behavioural surplus” unattainable with rivalrous commodities. This underscores a foundational divergence in the economic rationale of the digital epoch.

Crude Oil vs. Digital Data

| Characteristic | Crude Oil | Digital Data | Implication for the Data Economy |

| Scarcity | A finite, depletable resource created over millions of years. | Effectively infinite, generated at an exponentially increasing rate. | The core business challenge is not managing scarcity, but filtering signal from noise in an ocean of abundance. |

| Rivalry in Consumption | Rivalrous. Use by one entity prevents simultaneous use by another. | Non-Rivalrous. It can be used by countless entities and processes simultaneously without depletion. | Enables scalable business models where the same data asset can be monetised multiple times for different purposes. |

| Replication Cost | High. Cannot be replicated; only extracted and refined. | Near-Zero. Can be copied infinitely at virtually no cost. | Facilitates the frictionless spread of information and the creation of massive, redundant data repositories. |

| Transportation | Costly, physical, and resource-intensive process. | Instantaneous and low-cost via digital networks. | Removes geographic barriers to data access and enables the creation of a truly global data market. |

| Value Lifecycle | Depletes with use (e.g., burned as fuel). | Value often increases with use, reuse, and combination with other datasets. | Creates incentives for data aggregation and long-term storage, as its future value may exceed its current value. |

| Nature of “Spills” | Environmental and physical damage (e.g., ecosystem destruction). | Social, economic, and psychological harm (e.g., identity theft, manipulation, discrimination). | The negative externalities of the data economy are societal and intangible, making them harder to quantify and regulate. |

| Source | Extracted from the natural environment. | Generated from human experience and behaviour. | The raw material of the data economy is inextricably linked to human lives, raising fundamental ethical and rights-based issues. |

Spills and Scandals: The Dark Side of the Comparison

Despite their economic distinctions, both data and oil generate comparable detrimental effects. For instance, just as the environmental damage caused by oil spills (e.g., Exxon Valdez) occurred with limited industry accountability, data breaches (e.g., Cambridge Analytica) similarly corrupt information and diminish public trust. Moreover, notwithstanding public remonstrance, both industries continue to prosper, thereby illustrating societal reliance and corporate impunity. Consequently, this enables influential oil and technology corporations to externalise adverse repercussions while sustaining profitability. In doing so, they frequently disregard public welfare and, ultimately, encounter minimal accountability.

5. The Engine of the Data Economy: Surveillance Capitalism as a Business Model

To understand why data is as valuable as oil, we need to go beyond just collecting it. We must look at the economic system that turns data into profit. The main business model of the digital age isn’t just about using data to improve services or sell ads. It introduces a new economic logic. Harvard Business School professor emerita Shoshana Zuboff calls this “surveillance capitalism.” This model marks a significant shift from industrial capitalism. It creates a new level of power based on predicting and changing human behaviour.

Platform Revenue Comparison

| Platform | Revenue per US User (Annual) | Global Revenue per User | How Data Drives Value |

| $217 | $42 | Targeted advertising | |

| $460 | $61 | Search, ads, analytics | |

| Data Brokers | $700 (avg. est.) | $42–$263 (est. range) | Resale, analytics, profiling |

Beyond Advertising: A New Economic Logic

Surveillance capitalism, as conceptualised by Zuboff, is an economic framework wherein human experience serves as the foundational raw material for the extraction, prediction, and subsequent commercialisation of data. This system originated from Google’s imperative for profitability following the dot-com collapse. Google initiated the practice of leveraging “data exhaust” derived from user searches to forecast advertising click-through rates. This pioneering approach, which transformed user data into a valuable asset, established a novel marketplace and significantly propelled Google’s revenue expansion, demonstrating a growth of 3,590% between 2001 and 2004. This model became the Silicon Valley standard, notably after Sheryl Sandberg introduced it to Facebook in 2008.

6. The Supply Chain of Human Experience

The operational model of surveillance capitalism can be seen as a new type of supply chain that processes human experiences instead of physical goods. It has three key components:

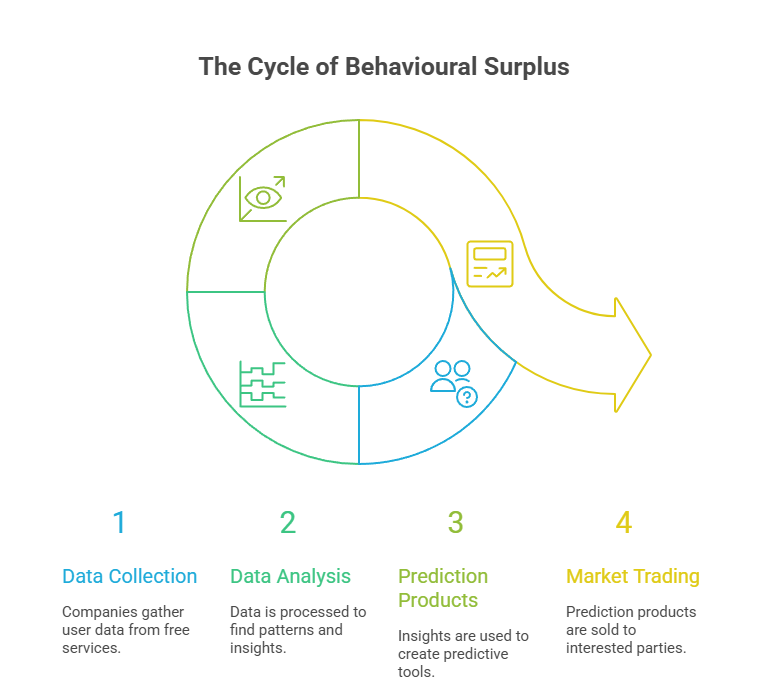

- Behavioural Surplus: This is the main idea. While offering a “free” service like search, social media, or navigation, companies collect much more data than they need to provide and improve these services. This excess data includes our clicks, likes, shares, search queries, location history, time spent on a site, facial expressions, and even the tone of our voice. This data is called behavioural surplus. Companies take it as their raw material without getting meaningful consent or compensation from users.

- Prediction Products: The behavioural surplus is then channelled into machine intelligence and AI algorithms. These systems look for patterns and connections in the data to create sophisticated prediction products. These are not just reports or insights; they are computational tools that make strong predictions about our future behaviour, such as what we might do soon or later. They can answer questions like, “What is the chance that this user will buy a new car in the next 90 days?” or “Which political message is most likely to sway this user’s opinion?”

- Behavioural Futures Markets: Finally, these prediction products are sold in a marketplace that Zuboff calls behavioural futures markets. Similar to markets that deal in oil futures or pork belly futures, these markets trade on expected human behaviour. The buyers in these markets are not the users of the “free” service; they are other businesses, like advertisers, insurance companies, landlords, political campaigns, and financial institutions, which have a strong interest in knowing and influencing our next actions.

7. From Monitoring to Modification

The competitive dynamics of behavioural futures markets create a strong economic incentive. A company that can predict behaviour holds value, but one that can guarantee it is immensely valuable. This has led to the shift from surveillance capitalism as a passive activity to an active one focused on behaviour change, a transition data scientists call actuation. The aim is now more than just knowing our actions; it involves intervening in our experiences to influence and alter our behaviour toward the most profitable outcomes, often through subtle cues that our awareness does not catch.

8. This “instrumentarian power” appears in several forms:

- Hyper-Targeted Advertising: This is the most common and obvious type of actuation. It uses detailed behavioural and psychographic profiles to deliver tailored ads that reach individuals at their most receptive moments, encouraging purchase.

- Algorithmic Curation and Engagement Maximisation: Social media feeds, video recommendations (such as YouTube’s algorithm), and news aggregators do not act as neutral sources of information. Carefully designed to maximise user engagement (time on site, clicks, and shares). By controlling the flow of information, these systems can subtly influence users’ moods, opinions, and views of reality.

- Real-World Herding and Gamification: This model goes beyond digital interaction and into the real world. The augmented reality game Pokémon Go, developed by Google, is an example. The game’s design directed millions of players to particular real-world locations—restaurants, coffee shops, retail stores—that were paying to attract guaranteed foot traffic.

- Massive-Scale Contagion Experiments: The potential for behaviour change has been tested directly. In 2012 and 2013, Facebook ran controversial experiments on hundreds of thousands of users, manipulating the emotional tone of their news feeds to determine if it could change their real-world feelings and posting habits. The study, published in a scientific journal, showed it could, proving the ability to create emotional influence on a large scale without users’ knowledge or consent.

This shift from monitoring to actuation shows that surveillance capitalism is not just a new market. It represents a new kind of power. The ability to shape behaviour across a population, operating discreetly within digital systems and lacking democratic oversight, creates a form of private governance that challenges core principles of individual freedom and self-determination, which are essential to a democratic society.

9. The Monetisation Machine: How Value is Realised

The core concept involves surveillance and control, which translates into value through internal and external monetisation strategies.

- Internal Monetisation: This involves using collected data to improve a company’s operations and profits. This is the most common and widely accepted form of data use. Examples include:

- Process Optimisation: Using data to make supply chains more efficient, manage inventory, or improve transportation logistics.

- Personalisation and Customer Experience: Using user data to create personalised recommendations. Amazon’s recommendation engine leverages behavioural data to generate an estimated 35% of its sales.

- Targeted Marketing and Upselling: Identifying existing customers who are most likely to respond to a new product or an upgrade and targeting them with specific marketing campaigns.

- External Monetisation: This involves selling data-derived products to third parties, which is at the heart of the behavioural futures market. This can take several forms:

- Data-as-a-Service (DaaS): Selling access to raw, aggregated, or segmented datasets. This can be a one-time sale or a subscription service.

- Insights-as-a-Service: Selling the analytics and insights derived from the data rather than the raw data itself. Meta for Business, which provides advertisers with detailed performance analytics on their campaigns, is a key example.

- Data Brokering: This is the entire business model for companies like Acxiom and Experian. They gather large amounts of data from public records, loyalty card programs, social media, and other sources to create detailed consumer profiles. Businesses purchase these profiles for marketing and risk assessment.

These monetisation strategies, fueled by the logic of surveillance capitalism, have created a multitrillion-dollar data economy. They have turned human experience into a new and highly profitable asset class. The extraction and trade of this data now support the business models of the world’s most powerful corporations.

Calculating the True Cost: The Multifaceted Price of Privacy

The huge economic value produced by the data economy comes with a cost. The business model of surveillance capitalism focuses on extracting behavioural surplus and predicting human futures. This approach leads to significant negative impacts. These costs usually do not appear on corporate balance sheets; instead, individuals and society bear them. This “price of privacy” is a complex mix of harms that goes beyond simple monetary loss. It includes deep psychological distress, the erosion of democratic norms, and the deepening of systemic inequality. In this economic model, psychological stress, democratic decline, and algorithmic discrimination are not just unfortunate side effects. They are predictable, systemic costs of a business model that does not need to account for the societal damage it causes.

9. The Individual Ledger: Economic and Psychological Harms

For individuals, the costs of participating, often unknowingly, in the data economy are both real and deeply personal.

Direct and Indirect Economic Costs

In 2024, data breaches incurred an average cost of $4.88 million for companies, a financial burden subsequently transferred to consumers. Individuals experience pecuniary losses resulting from fraud, identity theft, and the illicit acquisition of intellectual property, all exacerbated by a thriving dark web market for compromised data. Furthermore, beyond the direct impact of breaches, individuals in the United States expend over $400 million annually on privacy-enhancing tools such as Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) and unlisted telephone numbers, in addition to dedicating significant time to managing unsolicited communications and privacy configurations.

More subtly, the data economy imposes indirect economic costs through algorithms that act as new gatekeepers to opportunity.

- Price Discrimination: Companies use detailed personal data to engage in dynamic pricing. They charge individuals different prices for the same product or service based on perceived willingness to pay, location, or other behaviours. This practice extracts maximum value from each consumer and can lead to unfair treatment, where some pay more simply because their data profile suggests they can or will.

- Algorithmic Gatekeeping: Biased algorithms used in crucial life decisions can have serious economic effects. Automated systems increasingly screen applicants for jobs, credit, insurance, and housing. AI systems trained on biased data can perpetuate economic inequality by unfairly denying opportunities to qualified individuals from marginalised groups. For example, Amazon’s AI recruiting tool discriminated against female applicants, and healthcare algorithms allocated fewer resources to Black patients due to biased data.

10. The Psychological Toll

Perhaps the most significant individual cost is damage to mental and emotional well-being. The constant, often unseen collection of personal data takes a major psychological toll.

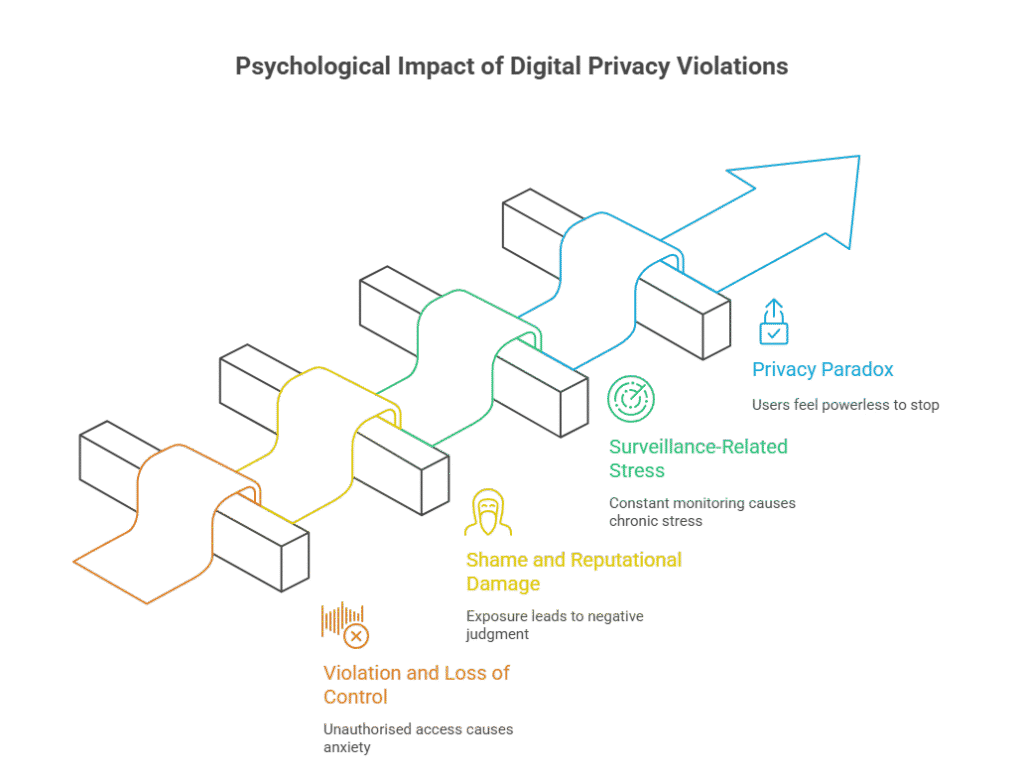

- Violation and Loss of Control: Privacy researchers and victims often liken a digital privacy violation to a physical home invasion. The unauthorised access and use of personal information, including conversations, movements, and search history, evokes a strong sense of violation and anxiety. This results in a lasting loss of control over one’s life and erodes the fundamental sense of security vital for mental health.

- Shame and Reputational Damage: The exposure of sensitive information through a data breach can lead to deep feelings of social shame, the fear of negative judgment from others, and moral shame, a sense of personal failure. This emotional distress can be severe and enduring, further complicated by the potential for reputational damage affecting personal and professional relationships.

- Surveillance-Related Stress and Paranoia: Awareness of constant monitoring can lead to chronic stress and paranoia. This can stifle self-expression and behaviour, as people become more guarded and less authentic, fearing that their actions or words could be misinterpreted or used against them.

- The Privacy Paradox and Learned Helplessness: Many individuals worry about their privacy but do not take sufficient action to protect it, known as the “privacy paradox.” This is not irrational but a symptom of a flawed system. Faced with unclear privacy policies and a lack of real choices, many users feel a sense of learned helplessness. The psychological struggle of knowing one is being exploited yet feeling powerless to stop it is a significant, though often overlooked, cost of the current data ecosystem.

The Societal Ledger: Democratic and Ethical Decay

The sum of these individual harms adds up to severe societal costs, threatening the foundations of democratic life and ethical behaviour.

Erosion of Autonomy and Democracy

The same methods of behaviour modification created for business purposes can easily be applied to politics.

- Manipulation of Public Opinion and Elections: The Cambridge Analytica scandal illustrated the use of behavioural surplus for political manipulation. By using detailed psychographic profiles taken from Facebook, the firm crafted and directed political messages aimed at influencing voter behaviour in the 2016 U.S. Presidential election and the UK’s Brexit referendum. This goes beyond persuasion into manipulation, undermining the idea of an informed and independent electorate.

- Erosion of the Public Sphere: Algorithm-driven content selection on social media and video platforms maximises engagement, creating filter bubbles and echo chambers. This reinforcement of existing beliefs exacerbates social division, promotes misinformation, and undermines the shared reality essential for democratic discourse.

Algorithmic Injustice and Systemic Bias.

Biased algorithms, when deployed societally, perpetuate and exacerbate systemic injustice. They mirror biases in their training data, replicating and magnifying disparities from an inequitable world. The issue is not an AI malfunction, but its intended operation, embedding historical disadvantage into contemporary automated frameworks.

This shows itself in several ways:

- Facial recognition systems have much higher error rates for women and people of colour because they are trained on datasets mostly containing white male faces. This can lead to wrongful arrests and misidentification.

- Predictive policing algorithms, which use historical arrest data that mirrors biased policing, can result in the over-policing of minority neighbourhoods and create a cycle of discriminatory enforcement.

- Credit scoring and risk assessment models that use proxies for protected characteristics, like zip codes as a stand-in for race, can deny entire communities access to financial services.

A significant “big data divide” is materialising, fostering a disparity between entities possessing control over data systems and individuals classified by these systems, frequently without an avenue for redress. Disadvantaged communities disproportionately incur privacy burdens as their pre-existing disadvantages are automated and exacerbated.

Concentration of Power and Regulatory Capture

The data economy has led to a significant concentration of economic and political power in a few “Big Tech” firms. Companies like Alphabet, Amazon, and Meta have market capitalisations and global influence that surpass those of many countries. This concentration has several harmful effects on society:

- It stifles competition and innovation. Dominant platforms can buy potential rivals or use their control over data and infrastructure to keep their market position.

- It leads to great political power, allowing these corporations to lobby heavily against regulation, shape public policy to their advantage, and engage in regulatory capture. In regulatory capture, the regulators become tied to the industry they are supposed to oversee. This creates a situation where the rules of the data economy are set by its most powerful players, further strengthening their control.

The Hidden Labour: The Human Cost of the AI Supply Chain

The “price of privacy” encompasses the human cost associated with the AI and data economy. “Ghost workers” or “data workers” undertake monotonous data annotation tasks, such as labelling, transcribing, and categorising, to facilitate the training of AI models. Content moderators, frequently originating from developing nations, are engaged in the review of detrimental content for meagre remuneration and often lack adequate mental health support, thereby enduring considerable psychological stress. The automated data economy is predicated upon this concealed and frequently exploited labour.

Governance in the Age of Data: Regulation, Ownership, and Technological Solutions

As the social costs of the data economy have become clearer, a global discussion has started about how to manage this new area. The response has focused on three main points: creating legal frameworks, a heated debate about the idea of data ownership, and developing tools to reduce privacy risks. Together, these efforts mark the early steps of society’s attempt to control the negative aspects of surveillance capitalism and build a fairer digital future.

11. Privacy Economics Table

| Aspect | Cost | Benefit | Net Impact |

| Privacy Regulation (GDPR) | $1M+/year/company, lower innovation, concentration | Trust, reduced cyber loss, and consumer rights | Mixed, varies by sector/size |

| Personal Data Value | $0.01–$700/year/person | Advertising efficiency, innovation | Firm benefit dominates |

| Privacy Paradox | Users share for convenience vs. claimed concern | Personalised offers, convenience | Risk of manipulation, hidden cost |

The Ownership Debate: Who Controls the Data?

The regulatory efforts stem from a deeper, unresolved discussion about the nature of data itself. How society defines data—as property, a public good, or an extension of the self—greatly impacts the future of the digital economy. This conversation is not just a technical or legal matter; it is a debate over what society prioritises—market efficiency, collective benefit, or individual dignity.

- Model 1: Data as Personal Property. The “Own Your Data” paradigm advocates for individuals to possess and derive financial benefit from their personal data, possibly through the implementation of micropayment systems. Nevertheless, opponents contend that this approach trivialises privacy for negligible advantage, introduces intricate transactional processes, and overlooks the inherent interconnectedness of data.

- Model 2: Data as a Public Good. This perspective views data as a public good, most valuable when shared for societal benefit, such as in public health and urban planning, and to foster innovation. The challenge lies in establishing governance that maximises these benefits while protecting privacy and security.

- Model 3: Data Control as an Inalienable Right. This model aligns with GDPR’s philosophy: personal data control is a human right, not a commercial property right, tied to dignity and autonomy. The focus is on establishing robust rights and responsibilities for data managers, rather than ownership. The challenge lies in defining and enforcing these rights against powerful entities.

12. Technological Countermeasures: The Rise of PETs

In addition to legal and philosophical debates, a set of technical solutions called Privacy-Enhancing Technologies (PETs) has emerged. PETs are technologies designed to allow the use and analysis of data while reducing the risk of exposing sensitive information and following data protection rules. They provide a possible way to balance the need for data utility with the importance of data privacy.

Key examples of PETs include:

- Cryptographic Tools: These use mathematical techniques to safeguard data during its use.

- Homomorphic Encryption allows calculations to be done directly on encrypted data without needing to decrypt it.

- Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC) enables several parties to analyse their combined data without any one party exposing its raw data to the others.

- Zero-Knowledge Proofs let one party prove to another that they possess certain information without disclosing the actual information.

- Data Obfuscation and Anonymisation: These methods change data to eliminate or conceal personally identifiable information.

- Differential Privacy is a structured mathematical approach that adds calculated statistical “noise” to a dataset. This allows for aggregate analysis while making it impossible to identify an individual’s contribution. The U.S. Census Bureau notably uses it.

- Synthetic Data Generation involves creating fake datasets that keep the statistical properties and patterns of a real dataset but do not contain actual personal information. This makes them safe for training AI models and software testing.

- Distributed Analytics: This method processes data where it is stored instead of moving the data elsewhere.

- Federated Learning is a machine learning method where an AI model is trained across various decentralised devices, such as smartphones, without the raw data ever leaving those devices. Only the total model updates go to a central server, protecting user privacy.

Privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs) are increasingly employed for secure data sharing within sensitive sectors such as healthcare and finance, a trend driven by evolving regulatory requirements. Nevertheless, PETs should not be considered a comprehensive solution; rather, they serve as instrumental tools that augment existing legal and ethical frameworks. Their successful implementation can be intricate and demanding of resources, necessitating integration into a holistic management strategy that prioritises human rights and democratic oversight.

13. Conclusion: Navigating the Future of the Data Economy

This report re-examines the data economy, moving beyond the “data is the new oil” analogy. It argues that data is inexhaustible and non-rivalrous, unlike oil, leading to flawed strategies. The true driver is “surveillance capitalism,” which converts human experiences into unremunerated raw material for behavioural predictions. This system creates a significant “price of privacy,” harming individuals economically and psychologically, and society through democratic erosion, exacerbated biases, and power consolidation.

The Next Frontier: AI and IoT as Amplifiers

The convergence of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the Internet of Things (IoT) will likely amplify the trends discussed in this report. These technologies are not creating a new system; they are instead enhancing the existing logic of surveillance capitalism, broadening its scope and refining its techniques.

The Internet of Things ( IoT) will significantly expand the behavioural surplus supply chain, shifting data extraction from screens to our physical world. Smart homes, connected cars, health monitors, and smart city infrastructure will evolve into constant sensor networks, resulting in continuous, widespread, and largely invisible data collection. This will generate an overwhelming amount of intimate, real-world behavioural data, far exceeding current online data.

AI significantly advances surveillance capitalism by refining data processing and predictive capabilities. It also improves behavioural manipulation through personalised, real-time influence.

The combination of these technologies threatens to create an unprecedented level of surveillance and control. The line between the digital and physical worlds will blur, undermining our ability to think and act independently.

A Call for a New Social Contract

Our current governance methods are insufficient for the digital future. While technical solutions like PETs help, and regulations focusing on individual consent fall short, we need a new social contract. This contract must prioritise democratic values and human dignity over profit, requiring focused action on multiple fronts.

- For Policymakers: We need to challenge the core logic of surveillance capitalism, not just manage its harms. This requires moving beyond consent, legally banning harmful practices like market trading in predictions for essential services or political gain, and implementing strong antitrust measures against Big Tech. Governments must also support data governance models prioritising human rights and public interest over profit.

- For Businesses: Shift from short-term data monetisation to long-term, trust-based value creation. Integrate privacy-by-design into the core business, investing in PETs and ethical business models. Trustworthiness will be a brand’s most vital asset.

- For Individuals and Civil Society: Moving forward, we need to shift from individual passivity to collective action. This involves boosting digital literacy to help citizens understand monitoring systems. Crucially, we must advocate for stronger regulations, support privacy-focused options, and demand democratic oversight of the data economy.

The price of privacy is ultimately the price of a free and self-determining society. The data economy presents opportunities alongside the risk of exploitation via surveillance capitalism. We must leverage data’s benefits while protecting individuals from commodification.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you. https://accounts.binance.info/tr/register?ref=MST5ZREF

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good. https://accounts.binance.com/register-person?ref=IHJUI7TF

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you. https://www.binance.com/register?ref=IXBIAFVY

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Alright, been hanging out at luk88club. Things here get pretty hot! If you need some fun, check this out! luk88club

Downloaded the me88app app the other day. Pretty smooth so far! Handy to have it all on my phone. Check it out if you are always mobile. me88app

Right then, time to give this taigameb66clubapk a look-see. Heard it’s got some decent games. Let’s hope my luck’s in!

Yonovipapkbet.. Hmm, the ‘VIP’ tag is quite inviting! Is the app sleek and user-friendly? And are we talking serious high-roller action? Details: yonovipapkbet

Betwebluck, huh? It’s got potentials, I liked the interface and the overall feel is cool. Give it a try and see if it gives you luck. betwebluck

888bgay, fam! If you’re lookin’ for some entertainment, this is the place to be. Wide variety and always somethin’ new to try! 888bgay

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you. https://accounts.binance.info/da-DK/register-person?ref=V3MG69RO

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.