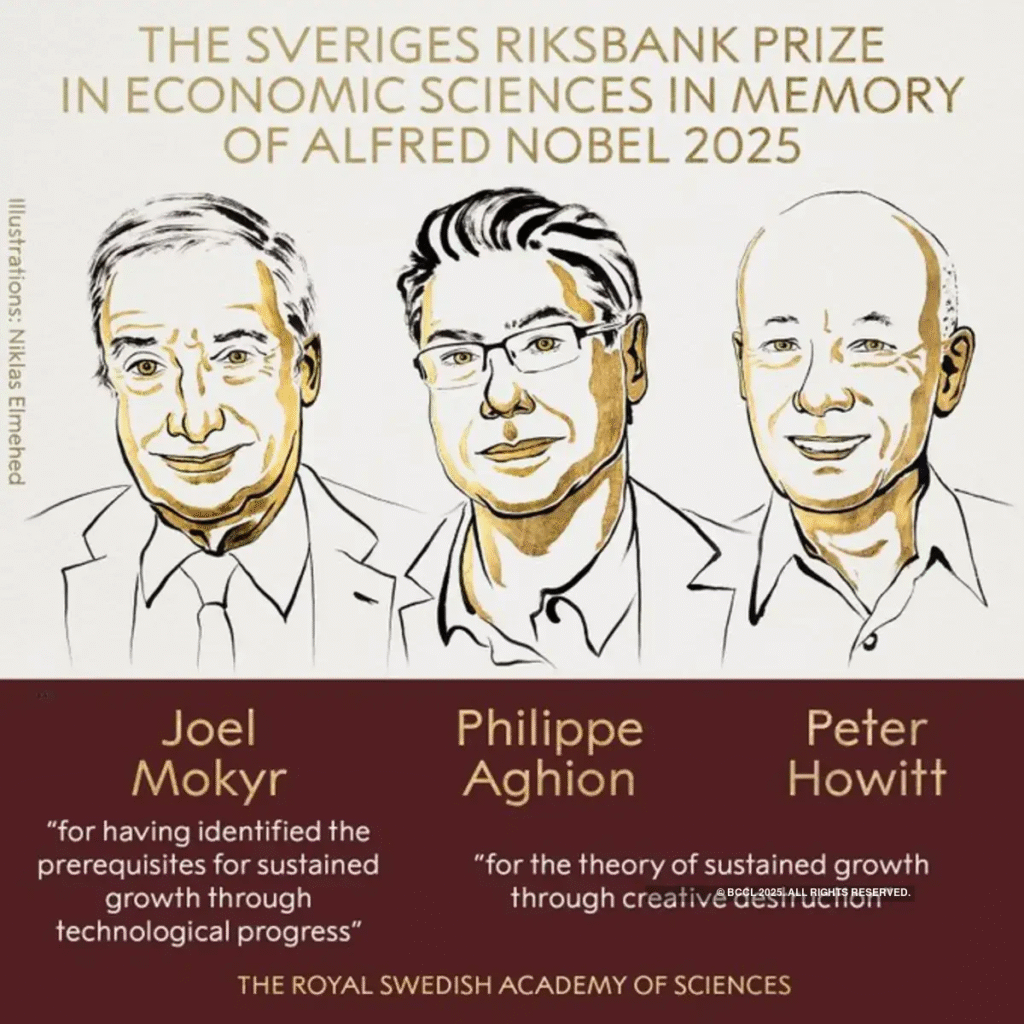

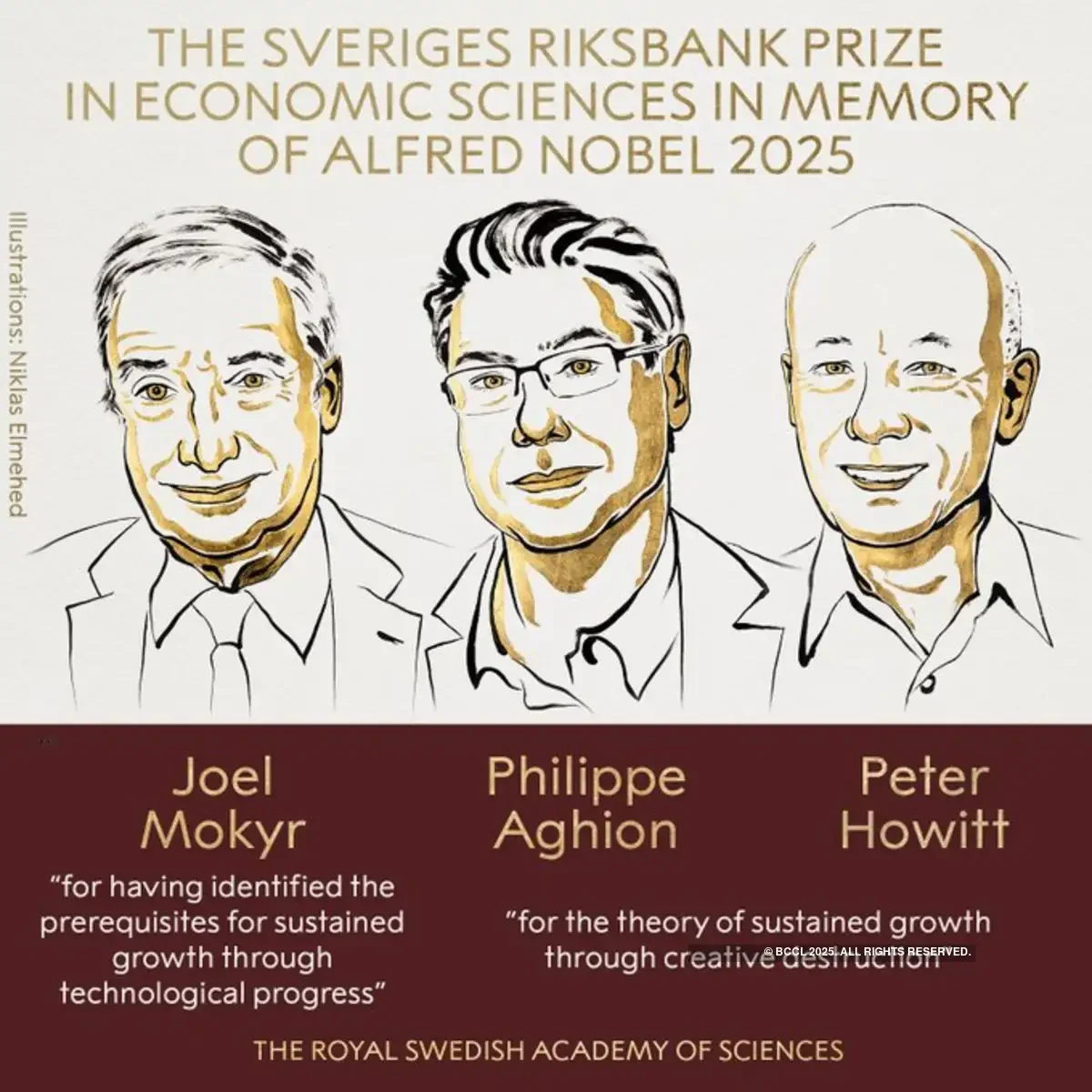

2025 Nobel Prize in Economics: Innovation-Driven Growth

This year, the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences went to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt “for explaining innovation-driven economic growth.” Mokyr, from Northwestern University and Tel Aviv University, received half the prize for “identifying the prerequisites for sustained growth through technological progress”. Aghion (Collège de France, INSEAD, and LSE) and Howitt (Brown University) were honoured. For their “theory of sustained growth through creative destruction,” they share the award. In short, the laureates demonstrated how new technologies replace older ones, driving long-term economic growth and improving living standards.

The award was given out during a lively discussion about innovation, trade, and productivity. Particularly in light of the growing influence of artificial intelligence. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences reminded us that continuous growth isn’t a given, as economic stagnation has persisted for thousands of years. The laureates’ work serves as a crucial reminder that society’s support for innovation is vital to keep progress moving forward. Committee chair John Hassler stressed, “We need to nurture the processes that foster creative destruction to avoid slipping back into stagnation.”

The Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences: History and Prestige

The Nobel Economics Award, also known as the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, is a very prestigious award established in 1968 by Sweden’s central bank. Unlike the original Nobel Prizes, which started back in 1901, this particular prize was first handed out in 1969 to Ragnar Frisch and Jan Tinbergen. It follows the same selection process and ceremony as the other Nobel Prizes. Every October, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences reveals the economics winners based on recommendations from a committee of experts.

The winners receive a cash prize of 11 million SEK in 2025, which is roughly $1.2 million, along with gold medals and diplomas. In 2025, the award will be presented in Stockholm alongside the other Nobel laureates on December 10. To date, 99 economists have been honoured with the prize across 57 awards, with only three of them being women. Winning a Nobel Prize in Economics is regarded as the pinnacle of achievement in the field, acknowledging work that has a profound and lasting influence.

- Origins: The prize started with a generous donation from the Swedish central bank in 1968, which celebrated its 300th anniversary. The first award was given in 1969.

- Selection: Nominations are thoroughly reviewed by the Economic Sciences Prize Committee, and the final winners are chosen by majority vote from the Academy.

- Ceremony: On Nobel Day, December 10, in Stockholm, winners receive medals and diplomas, and they share the prize money.

Meet the Laureates: Mokyr, Aghion, and Howitt

- Joel Mokyr (b. 1946) is a Dutch-born economic historian at Northwestern and Tel Aviv Universities. He studies why the Industrial Revolution started in Europe and how technology drives economic growth. He blends history, economics, science, and culture. Mokyr highlights three conditions for ongoing growth: useful knowledge, mechanical skills, and supportive institutions. He argues that strong scientific knowledge, practical engineering, and an open society fueled innovation and income growth. His books, such as The Lever of Riches, Gifts of Athena, The Enlightened Economy, and A Culture of Growth, explore how Enlightenment ideas sparked the modern economy.

- Philippe Aghion (b. 1956) is a French economist at Collège de France, INSEAD, and LSE. He is known for his work on growth theory and innovation. He earned his PhD at Harvard in 1987 and studied how firms and competition stimulate innovation. Aghion coined the term “Schumpeterian growth” for models that focus on creative destruction, based on Joseph Schumpeter’s idea that capitalism grows by constantly replacing old industries. With Howitt, Aghion created formal mathematical models to describe these dynamics.

- Peter Howitt (b. 1946) is a Canadian economist at Brown University (USA). He worked closely with Aghion on many papers, including the important 1992 article. He earned his PhD in economics from Northwestern in 1973 and has contributed to macroeconomics and growth theory. Together, Aghion and Howitt turned the abstract idea of creative destruction into a concrete model with equations.

All three laureates have dedicated their careers to understanding growth: Mokyr through historical narratives and data, and Aghion and Howitt through formal economic modelling. In announcing the award, the Nobel committee noted that technological innovation drives further progress and credited these economists with clarifying how and why innovations have led to centuries of growth.

Core Ideas Behind the Award-Winning Work

Mokyr’s Theory of Sustained Growth

Joel Mokyr’s contribution to growth theory reveals why modern economic growth became self-sustaining after centuries of stagnation. He identified the missing ingredients that finally came together during the Industrial Revolution, transforming occasional invention into a continuous process of technological progress.

According to Mokyr, three key factors enabled this transformation:

Useful Knowledge — Scientific and technical understanding that explains how the world works.

Mechanical Competence — The craftsmanship and engineering skills to turn ideas into machines and production systems.

Openness and Supportive Institutions — A social and institutional environment that values curiosity, rewards innovation, and tolerates disruption.

Before the 18th century, these elements rarely coexisted. Scientific discovery was often separate from practical application, and rigid political or cultural systems stifled new ideas. Enlightenment Europe, especially Britain, changed this trend. A culture emerged where theory and practice supported each other, linking experimental science with industrial application. This feedback loop made innovation cumulative rather than accidental.

Mokyr’s insight is that modern growth began when societies not only invented but also understood their inventions. Scientific reasoning allowed innovations to build on one another, creating what he called a “culture of growth,” a self-reinforcing system of progress. His research shows that when useful knowledge, technical skills, and open institutions interact, technological advancement becomes an unstoppable force.

In essence, Mokyr explained the cultural DNA of economic growth: knowledge drives invention, invention requires skill, and both thrive only within open, curiosity-driven societies. His work complements Aghion and Howitt’s theory of creative destruction by highlighting the deeper foundation that makes such renewal possible. Together, their insights show that sustained progress is not just an economic process; it is a cultural achievement rooted in how societies think, learn, and evolve.

Aghion & Howitt’s Creative Destruction Model

Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt turned Joseph Schumpeter’s idea of creative destruction into a clear and measurable theory of economic growth. Their 1992 model showed how competition driven by innovation fuels long-term development and why destroying the old is necessary for creating the new.

By mathematically modelling the “ladder of innovation,” Aghion and Howitt illustrated how firms, motivated by monopoly profits, keep investing in R&D to climb higher. However, each innovation also replaces older technologies, reflecting Schumpeter’s insight that capitalism’s strength comes from its ability to renew itself. This tension between creation and destruction explains how modern economies evolve, change, and sustain growth over time.

The model’s strength lies in its balance: too little innovation slows progress, while too much “business stealing” can lead to socially inefficient growth. This insight connects the behaviour of individual firms with broader economic outcomes, giving policymakers guidance on how to support balanced, sustainable growth. Effective policies like R&D incentives, antitrust enforcement, education reform, and innovation-friendly regulations can ensure that creative destruction benefits everyone, not just the leading firms.

In short, Aghion and Howitt provided the mathematical foundation for Schumpeter’s intuition, proving that capitalism’s long-term vitality relies on a system that is willing to replace itself. Their model remains essential in modern growth economics, reminding us that innovation drives progress while also disrupting it.

Key Evidence and Methods

Mokyr’s evidence is mostly historical and qualitative. He uses economic history, case studies of major inventions, and data on incomes, trade, and education to argue which factors mattered. For example, he refers to archival records of scientific progress and changes in institutions, such as patent laws and universities, from the 18th to 19th centuries, to show how knowledge spread. One Nobel summary states that Mokyr used historical sources to uncover the causes of sustained growth, becoming the new normal. He treats economic history as a large experiment. He compares different eras and places with varying levels of knowledge, skill, and openness to identify what led to growth.

In contrast, Aghion and Howitt took a theoretical approach. Their 1992 article in the Quarterly Journal of Economics was a purely mathematical model. They used principles about innovation, derived from data and previous theories, to create a set of equations. They then explored the model to see how factors like R&D spending, firm profits, and growth interact. The Nobel committee explains that in their 1992 article, they constructed a mathematical model for what is known as creative destruction. This model has testable predictions, such as how growth rates relate to competition and R&D intensity, which later research has evaluated.

Together, the laureates combine qualitative insights from Mokyr with formal theory from Aghion and Howitt. They do not rely on conducting experiments or natural experiments. Instead, they present frameworks: Mokyr’s framework is based on historical data, while Aghion and Howitt’s framework is rooted in economic theory. Both contribute to understanding by organising numerous ideas coherently.

Creative Destruction: Explained in Plain Terms

The central message from Schumpeter, Aghion, Howitt, and Mokyr is straightforward but significant. Innovation drives growth by constantly replacing the old with the new. This process of creative destruction transforms economies, industries, and living standards over time.

Creative Destruction in Action

In an economy fueled by innovation, companies compete not by simply improving existing products, but by bringing something new to the market. When a business launches a better product or process, it makes older technologies outdated. The automobile took over from the horse carriage, streaming services replaced CDs, and e-commerce changed traditional retail. These are not just shifts in business; they represent structural changes that promote long-term prosperity.

Why Growth Requires Destruction

Sustained growth relies on ongoing renewal. If powerful firms or outdated organisations prevent innovation, economies can stagnate. As Nobel laureate John Hassler pointed out, “We must uphold the mechanisms that underlie creative destruction, so that we do not fall back into stagnation.” This means that while innovation creates both winners and losers, it also fosters progress, leading to improved living standards and fresh opportunities for the future.

The Innovation Ladder

Aghion and Howitt illustrated this concept with their well-known “ladder model.” Picture an economy as a ladder: each company climbs to the top by innovating and temporarily earning higher profits. However, no one stays at the top forever; another company soon develops something better and takes the lead. This ongoing race to the top keeps industries active and ensures that economies grow through competition, rather than complacency.

The Historical Turning Point

The Nobel committee’s data visualisation of GDP per capita in Britain and Sweden from 1300 to 2022 makes this trend clear. For centuries, income remained flat until the Industrial Revolution. After 1800, growth accelerated at about 1.5% each year, marking the moment when creative destruction and technological progress became forces that sustained each other.

Beyond GDP: Growth as Human Progress

Economic growth is more than just figures; it’s about improving lives. Innovations in medicine, energy, transportation, and communication have transformed well-being in ways that figures alone cannot capture. From vaccines and fertilisers to computers and the internet, technological progress has provided immense social value. As Joel Mokyr highlights, modern measures often underestimate the benefits of digital innovation—such as free apps, online learning, or music streaming—which enhance daily life without always directly increasing GDP.

The Balance of Forces

Aghion and Howitt’s framework highlights two competing forces that shape the ideal pace of innovation:

Private Incentive: Companies innovate to make profits and maintain their edge.

Social Value: Society gains from shared knowledge, even as technologies become outdated.

This dynamic illustrates why public policies—such as R&D funding, fair competition, education, and institutions that encourage knowledge sharing—are vital for balancing the immediate disruption of creative destruction with its long-term advantages.

The Cultural Foundation of Progress

Joel Mokyr’s historical perspective adds depth to this economic model. He showed that lasting growth began only when knowledge, skills, and open institutions came together to create a “culture of growth.” When societies understood not only how innovations worked but also why they worked, science and industry developed a feedback loop that drove centuries of progress.

Implications, Critiques, and Open Questions

The work of the laureates has significant implications, but it also has limitations and leads to debates:

Advances in Theory:

Aghion and Howitt’s model has improved on earlier growth theories, such as Solow’s and Romer’s, by showing that new ideas can make old ones obsolete. It illustrates how competition and innovation drive growth in equilibrium. Mokyr’s historical approach fills in gaps by highlighting cultural and institutional factors that purely mathematical models might overlook. Together, their contributions ground the idea of innovation-driven growth in both facts and formulas.

Practical Insights:

One important lesson is that economies need mechanisms, such as markets, competition, and intellectual freedom, to enable creative destruction. If monopolies or regulations overly protect old industries, innovation slows down. This aligns with Schumpeter’s warning that capitalism without creative destruction could stagnate. Aghion and Howitt explicitly show that too little competition can result in too little innovation. This insight raises modern concerns about large tech companies; highly dominant firms may hinder the next generation of startups. As one laureate noted, growth is not guaranteed if “today’s innovators will stifle future entry.”

Challenges and Criticism:

No theory is flawless. Critics argue that these models simplify the real world. For instance, Aghion and Howitt assume a single type of innovation and overlook finance, politics, or resource limits. They also assume that R&D easily converts into new products, which may not always be true. While Mokyr’s approach provides rich historical insights, it mainly describes what happened rather than predicting outcomes like a model. Furthermore, economic growth can have complex side effects, such as increasing inequality or harming the environment. Aghion and others have emphasised that continuous growth is not necessarily beneficial if it harms the planet.

Open Questions:

The laureates’ work raises many questions. For instance, what is the right balance between competition and stability? How much should governments fund R&D or education? If growth inevitably displaces jobs in certain sectors, how can we best support affected workers, perhaps through retraining or flexible policies? Additionally, in today’s context, will artificial intelligence lead to a new wave of creative destruction and growth, or will it create new forms of lock-in? Philippe Aghion has pointed out that we may be at a crucial turning point with AI, warning that “some superstar firms may end up dominating everything and inhibiting the potential entry of new innovators.” These questions present active areas for future research.

Real-World Relevance and Impact

These theories are more than just academic; they help explain many real trends in modern economies. For policymakers and business leaders, the message is clear: fostering innovation is important, but so is managing its disruptive effects.

Economic Policy:

The laureates suggest that deregulation and competition policy promote growth. Policies that lower barriers for new firms, such as fair antitrust enforcement, may encourage more creative destruction. In contrast, heavy protection for established companies can hinder growth. Aghion has noted that rising trade barriers, such as tariffs and monopolistic practices, are serious threats to growth. Similarly, government support for basic research and education can foster the key elements Mokyr identified: knowledge and mechanical skills.

Business Strategy:

For entrepreneurs and corporations, these insights emphasise the importance of ongoing innovation. Even successful firms must keep investing in research and development, or they risk being outcompeted. Many well-known examples highlight this: Blockbuster vs. Netflix, Kodak vs. digital cameras, and horse carriage makers in the early 20th century. These stories illustrate the idea that companies must either disrupt or be disrupted.

Society and Workers:

The analysis also shows that innovation creates both winners and losers in the short term. A new technology can eliminate certain jobs or business models. The laureates and commentators argue that societies should focus on protecting workers, not jobs. This could involve retraining programs, social safety nets, or policies to ease worker mobility. Aghion and Howitt’s later work suggests that systems like flexicurity, which facilitate job transitions, can help ease the shift.

Case Studies:

Recent events illustrate the theory. The growth of e-commerce and streaming services is are clear example of creative destruction. On a larger scale, economies that embraced innovation, such as the US after World War II or China since the 1980s, experienced rapid growth. In contrast, regions resistant to new technology often fall behind. The laureates’ findings suggest that to maintain their economic advantage, countries must invest in research and education, keep markets open, and promote competition.

Global Challenges:

Innovation-driven growth also relates to global issues. For example, the shift to renewable energy represents a form of creative destruction: older fossil fuel industries will decline as green technologies, like solar panels and electric cars, grow. Understanding these dynamics can help balance economic growth with environmental objectives. Aghion and Howitt’s framework can be used to examine whether new green-tech monopolies might slow down or accelerate this transition.

Looking Ahead: Future Research and Policy Suggestions

Building on these ideas, future economists and policymakers might explore:

- Innovation and AI: Many expect artificial intelligence to trigger a wave of creative change. The laureates themselves pointed out AI’s potential. Researchers could extend Aghion and Howitt’s models to consider digital networks, data monopolies, or AI-generated innovation. Questions include: Will AI make knowledge spread faster? Or will it concentrate power among a few tech giants?

- Measuring Growth Beyond GDP: As Mokyr emphasises, some modern innovations have significant social value but little impact on GDP (e.g. open-source software, online education). Future work might develop new measures of well-being or productivity that recognise these changes.

- Balancing Inequality: If innovation increases inequality (since not everyone benefits equally), how can we design policies to share the benefits? Aghion and others have suggested that growth-friendly policies should be combined with redistribution or education efforts.

- International Convergence: Mokyr’s comparative-historical perspective raises the question: Can late-developing countries create the same innovation ecosystem? What institutions do they need to replicate the success of early innovators?

- Competition and Regulation: Empirical researchers can test A&H’s predictions by examining how market concentration influences innovation rates. The Nobel work suggests that moderate concentration is optimal; having too few firms or too many is detrimental to growth. Policymakers in antitrust agencies may use these insights to establish merger guidelines or enforce antitrust laws.

- Technological Spillovers: How do new ideas build on old ones? Mokyr’s notion of a self-generating process could inspire more research on knowledge networks, patent citations, and the social dynamics of science.

Conclusion: Key Takeaways

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics celebrates more than just three scholars; it honours a century of ideas explaining how innovation drives economic growth. Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt each uncovered a different part of the same puzzle: why progress occurs, how it continues, and what risks it faces.

- Joel Mokyr explained why the modern world began to grow. When knowledge, skills, and open institutions came together during the Industrial Revolution, it created a “culture of growth.”

- Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt described how growth maintains itself through creative destruction. This constant cycle sees new ideas replace old ones, boosting productivity, prosperity, and renewal.

Their work sends a timeless message for our time:

- Innovation fuels prosperity, but doesn’t happen by itself. It needs support from science, education, entrepreneurship, and helpful institutions.

- Disruption is not the enemy of progress; it is its engine. As new technologies arise, old industries disappear, and societies must adjust to embrace change instead of fearing it.

- Policy sets the speed of progress. Governments must find a balance between competition and protection, supporting research and development, innovation ecosystems, and skill transitions for workers affected by change.

- Complacency is the real danger. Without ongoing innovation, economies risk stagnation. The same forces that initiated past revolutions, from steam to silicon, will influence future ones, from AI to clean technology and biotech.

For students, policymakers, and curious readers, this Nobel recognition serves as a reminder that growth is both creative and destructive. Its success depends on how well societies foster invention while addressing its disruptions.

The story of Mokyr, Aghion, and Howitt ultimately tells us that progress is not guaranteed. It requires effort through curiosity, courage, and a commitment to continually reinvent the world.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you. https://www.binance.info/zh-CN/register?ref=WFZUU6SI

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good. https://accounts.binance.com/kz/register-person?ref=K8NFKJBQ

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me. https://accounts.binance.com/fr/register?ref=T7KCZASX

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?